Reactive MVC and the Virtual DOM

The web frontend scene is witness to many new frameworks and ways of working. It can be quite annoying when software becomes legacy quicker than ever. But actually, it's just good old innovation happening as it should, because the opportunities for improvement are there. Frameworks come and go, but what remains are the good ideas that they brought to the world. We're going to talk about the good ideas and the not so good ideas.

React is one of those currently hottest frontend technologies. The new great idea in React is Virtual DOM Rendering. The gist is to frequently re-render a complete and lightweight representation of the DOM, then apply a difference filter to detect the minimum changes that need to be made to the DOM. A similar technique has existed in game development long before React: re-render the game screen in every game loop, but only update the minimum portion of the screen which changed compared to the previously rendered screen.

It's hard to speak about React without mentioning Flux, because only with both together can we speak of a complete frontend architecture, since React concerns only user interfaces. Flux contains many ideas, but it can be summarized as an architecture with a unidirectional and circular flow of data. The benefit is code that is easier to follow with regard to data updates.

I started applying React to a tool I built called RxMarbles.com, and spent some time investigating Flux. React turned out to disappoint me in multiple ways, mainly through a poorly designed API which induces the programmer to create complex state machines and to mix multiple concerns in one component. I decided to replace React with the great virtual-dom library, and to build a Reactive MVC alternative heavily based on RxJS. This pattern turned out to be successful and I applied it to other web apps. One of these is a customer project we are glad to say has worked out very well.

The combo React/Flux is clearly inspired by Reactive Programming principles, but the API and architecture are an unjustified mix of Interactive and Reactive patterns. Keep reading and I'll explain what this means, and how we can do better.

Duality in inter-module communications

Duality is an old and powerful concept that we sometimes encounter in Mathematics, but also in programming. In a nutshell, some problem might be cumbersome to work with under one perspective, but under its dual perspective, it becomes easier.

A playful example of duality is the dark and light Hyrule worlds in The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. In the light world, one quest might be impossible to solve, and you need to go to the dark world to solve it, although both places are just different perspectives of the same space.

Light and Dark Hyrule in the Legend of Zelda: Link to the Past

Light and Dark Hyrule in the Legend of Zelda: Link to the Past

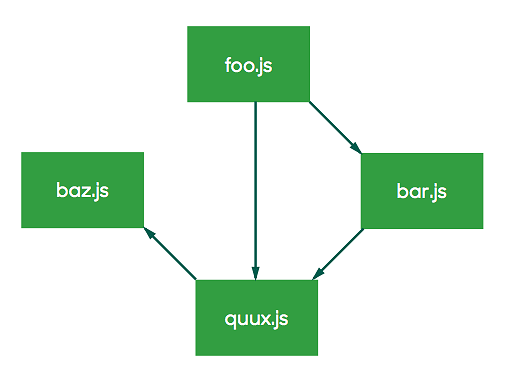

What is duality when it comes to components of an app communicating with each other? Let's assume you have a project built with browserify modules foo, bar, baz, quux, arranged as such:

An arrow from foo to bar means that foo somehow affects bar, by updating data in bar. A typical case is code inside foo which calls

bar.updateSomething(someValue);

Question: where does each arrow live in a program? They can't simply live in between modules, because all code is inside some module. The answer is: it depends, but typically, you expect the arrow to be defined in the arrow's tail, as such:

Arrows defined at their tails (Interactive)

Arrows defined at their tails (Interactive)

This paradigm which you have probably been doing for most of your career is called "Interactive Programming", defined in a paper from 1989. Reinterpreted to our context, we can define it as:

In the Interactive pattern, module X defines which other modules X affects.

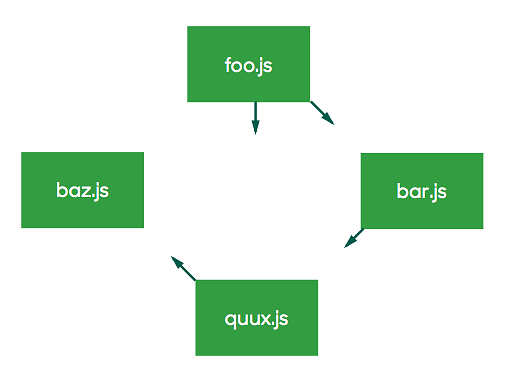

The dual of Interactive is Reactive, where arrows are defined in the opposite end, in the arrow head, as such:

Arrows defined at their heads (Reactive)

Arrows defined at their heads (Reactive)

That's it. Just flip the responsible parent for the arrows in this directed graph, and you get the Reactive pattern.

In the Reactive pattern, module X defines which other modules affect X.

The benefit of Reactive over Interactive is mainly separation of concerns. In Interactive, if you want to discover what affects X, you need to search for all such calls X.update() in other modules. However, in Reactive, all that it takes is to peek inside X, since it defines everything which affects it. For instance, this property is common in spreadsheet calculations. The definition of the contents of one cell are always defined just in that cell, regardless of changes happening on the other cells it depends on.

How to implement the Reactive pattern?

One common implementation of the Reactive pattern is to introduce event emitters. Hence, a module X can simply subscribe (or listen) to events from module Y in order to define that X is affected by data coming from Y. In this sense, Y is decoupled from X so that it doesn't need to consider X's existence. You do not need libraries such as RxJS or Bacon.js in order to implement this, and in fact, Flux and React use cases typically have EventEmitter from Node.js.

When all modules start using event emitters as basic building blocks, you need an intelligent way of handling event emitters. For instance, what do you do when you need to define one event emitter as the 1-second delayed version of another event emitter? The answer probably floats around a state machine based on setTimeout() and clearTimeout(). And what if you need to merge two event emitters? There clearly is a need for higher-order functions over event emitters so one can, for instance, simply construct an event emitter y from x by writing

var y = delay(x, 1000 /* ms */);

The state of the art tools for higher-order functions over events, currently available, are RxJS, Bacon.js, and Kefir.js. I prefer RxJS for its language ubiquity, but your mileage may vary. EventEmitter compared to RxJS is analogous to roller blades versus cars.

How would a reactive module look like? It doesn't have imperative functions such as update(), and is based on RxJS Observables (our "event emitters"). As it turns out, the public interface of a reactive module consists only of Observables it exposes for the rest of the app to subscribe to. This reactive module might itself also need to subscribe to external Observables of other modules, so it either internally requires (node style imports) those modules, or it has a function for dependency injection.

For instance, below is an example of a "Notifications Center" module, which observes events from other modules and exports its own events based on those.

var breakingNews = require('myapp/breakingNews');

var sms = require('myapp/sms');

var notifications = Rx.Observable

.merge(breakingNews.newsEvents, sms.messageEvents);

module.exports = {

notifications: notifications

}

Reactive MVC?

What would an MVC-like architecture for single-page apps look like if all components were reactive? To start with, we need to get rid of the Controller, because it is by definition an Interactive component, imperatively controlling other components. In fact, no reactive component should send commands to other components in an imperative fashion.

The Model takes care of representing data and the current state of the app, so it should export Observables of data events. The View should subscribe to Model events and render a representation of the Model. The rendered output can also be wrapped as an Observable which the View exports. As it turns out, the View component is nothing else than a function which takes Model events as input and has renderings as outputs.

The missing piece is the Controller replacement, as it usually happens with MV architectures. We need a component to take the responsibility of managing user input events. A traditional Controller would take user input events, do some computation over them, and then call a function such as Model.update(value). Because we are doing Reactive, it should go the other way around: the Model observes what the "Reactive Controller" wants* to update, and the Model decides to update itself based on "Reactive Controller" events.

The name I give to this Reactive Controller is "Intent".

Model-View-Intent

Intent is a component whose sole responsibility is to translate user input events into model-friendly events. It should interpret what the user is trying to do in terms of model updates, and export these "user intentions" as events. It translates "View idioms" to "Model idioms". Intent itself doesn't change anything else, as any other typical Reactive component doesn't, by definition.

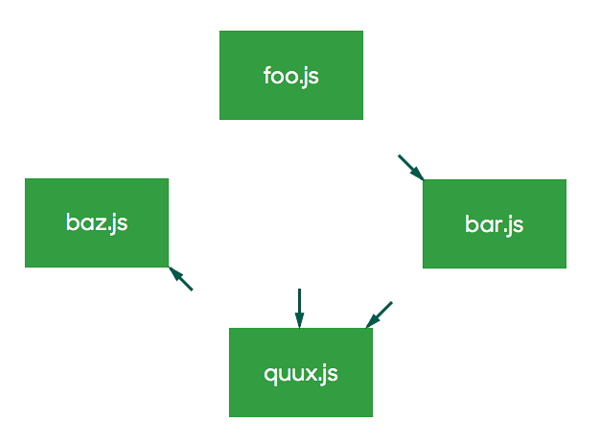

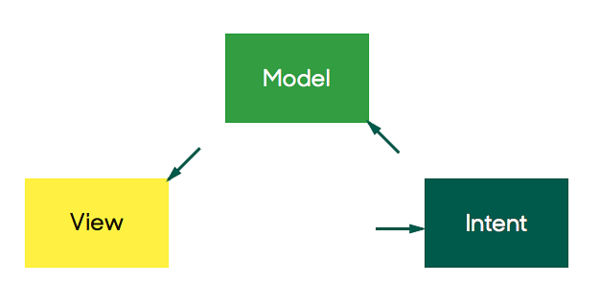

The Model observes Intent events, and decides to change its data if the intent doesn't break restrictions internally defined in the Model. This ties the knots of a circular unidirectional flow of data:

View observes Model, Intent observes View, Model observes Intent

View observes Model, Intent observes View, Model observes Intent

Each of these is "function-like", in the sense that it takes events as input and exports events as output. However, they cannot be JavaScript functions strictly speaking, because that would be a recursive cycle without a starting point. This is what each part has as inputs and outputs:

Model

Input: user interaction events from the Intent.Output: data events.

View

Input: data events from the Model.Output: a Virtual DOM rendering of the model, and raw user input events (such as clicks, keyboard typing, accelerometer events, etc).

Intent

Input: raw user input events from the View.Output: model-friendly user intention events.

To avoid circular imports, we cannot use require from Node.js. Instead, each of these components has an observe() function as a dependency injection mechanism to define what is its input module. For instance, view.observe(model);. To tie all the knots, we instantiate the three, and then call the three observe() functions along the cycle. To see how this works in practice, check out this example.

To have inter-model dependencies, one Model just needs to import other Models and listen to their events. The same applies to dependencies between Intents.

Virtual DOM to DOM

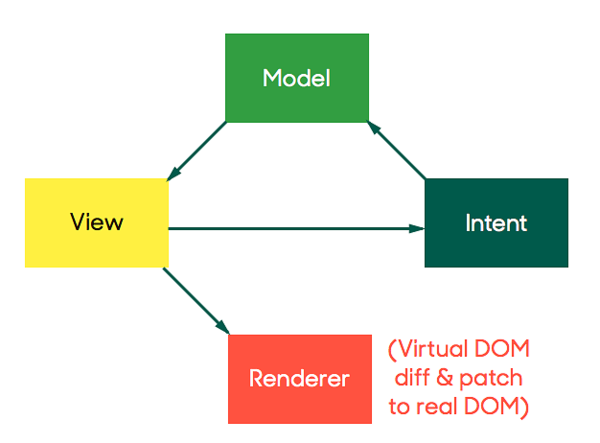

Reactive components by definition do not change the external world, so the MVI trio won't either. For changing the external world we need side effects. It might come to you as a surprise, but in this MVI architecture, the View doesn't actually render anything to the user. View exports an Observable of VTree, which is in virtual-dom terminology just a virtual DOM "element". View's responsibility is to express what the DOM should look like, but it doesn't itself change the DOM.

We delegate the responsibility of changing the DOM to a component called Renderer. It's very simple: it subscribes to VTree Observables from all the Views in your app, and converts these VTree into actual DOM elements. It does so by diff'ing with the previous VTree and applying a patch to the DOM.

Renderer component as a side effect

Renderer component as a side effect

Renderer is a side-effect and "sink" type of component, consuming events from Views and changing the real world. The benefit of its separation from Views is that Views become more testable since they don't require a browser environment. You can use Views as function-like components: feed in any mockup data, and inspect what Virtual DOM elements (just Javascript objects) come out.

Apparently, React has only renderToString() (meant for using from the backend), which isn't the best format for testing output views. In MVI it is easier to test purely virtual elements.

Example

A couple of weeks ago I saw this collection of React examples, and decided to build one of those implemented in MVI and Virtual DOM. You can compare it to its React counterpart.

How is this different to React/Flux?

MVI is a unidirectional data flow architecture with Virtual DOM for rendering, just like React/Flux is. But the similarities end there, and MVI is different for the following reasons.

Purely Reactive. React mixes Reactive programming patterns with Interactive programming patterns, whenever it makes use of imperative APIs such as setState, forceUpdate, setProps, render. Flux attempts to be reactive by making Stores listen to Dispatcher events, and Controller-Views listen to Store events. However, the centralized Dispatcher is imperatively controlled by Actions, rather than taking the responsibility to observe Actions. Also, Actions are imperatively created at Views. MVI has a consistent reactive approach, making it easy to reason how any component is internally structured.

MVI is decentralized. Flux has a centralized Dispatcher, and the guidelines recommend that it is kept always singleton in the application. This leads to typical centralization problems such as unmaintainability of a large file as the application grows. The Dispatcher is actually an event plumber, connecting all the parties related to events, in a style not that different to a centralized Event Bus. In the MVI structure described here, inter-model dependencies can be easily described separately in each Model: whenever Model X depends on events from Model Y and Model Z happening first, then X simply internally defines that it depends on Y and Z.

Leverages the power of RxJS. While Flux suggests using the low-level EventEmitter which requires manual event handling, RxJS and similar event processing tools are powerhouses capable of replacing a lot of boilerplate that a typical Flux application contains. RxJS also allows the internal structure of a component to be reactive.

Renderer separated from View. By separating View logic from View rendering, the application has more separation of concerns, and the View becomes more testable and replaceable. Since the Renderer is modular and never referenced by any other component, one can also play with different implementations of the Renderer and easily swap between them. In a Renderer, you can even have post-processing steps over the View Observables, modifying the elements or wrapping them in a container div. This makes it easy to implement UI skins, for instance. These modular capabilities do not exist in React.

More testable. Every component in MVI, except side-effects such as the Renderer, are function-like since they are free of side-effects and receive input, generating output. This is an ideal situation for automated tests, specially when the View logic can be tested outside of a browser context, where test execution is faster.

Less coupled. Interactive patterns, often found in React/Flux, immediately imply more coupling between the parts. For instance, Actions import the Dispatcher and explicitly affect it, hence making it harder to replace the Dispatcher with another, if needed. MVI has separation of concerns in its core since it follows reactive programming principles strictly. You can even insert a mediator between the Model and the View or between any other two reactive modules, since they shouldn't need to explicitly import each other. Each component in the MVI cycle is agnostic to the input component it is given in the dependency injection system, as long as the input satisfies an expected interface.

virtual-dom is faster than React. Preliminary benchmarks show that rendering run with virtual-dom is faster than in React and other frameworks. I have yet to see React (as a Virtual DOM rendering tool) perform better than virtual-dom.

Models observe other Models. Flux dictates that inter-model dependency should live in the Dispatcher, but in MVI, those dependencies are defined inside each Model.

No internal state. MVI is comparable to React implementations that only use properties (no state). Views should not contain internal state, since that would violate the View concern, which is simply to render a virtual element. In MVI, all state should live in the Model, even those that are purely UI related. This is more of a recommended practice, rather than a limitation, since one has freedom to implement state in MVI Views. This is related to the next point.

No reusable UI components. React has a strong emphasis on "reusable UI components", which is unmatched in this current MVI proposal. The focus in MVI is to enable separation of concerns with function-like modules. Currently, achieving proper reusable UI components in MVI is still an open problem. That's because a React View component can contain all three Model, View, and Intent responsibilities. I believe the ideal solution to this will be the advent of Web Components inside the context of a Virtual DOM. Ideally, we should virtually render a custom-element, with its own internal state and complex behavior, just like we do with any other div. For a lengthy discussion on these possibilities, read more from our brilliant Jarno Rantanen.

What's next

Model-View-Intent might evolve into a framework, or might not require enough boilerplate to justify a framework. Problems are yet to be discovered. Currently, the biggest challenge is encapsulating a UI component with its behavior, for reuse. We are anxious to see what Web Components will enable together with a Virtual DOM.

I strongly recommend frontend developers to try virtual-dom before picking up React. Its API is minimal, and it only does one thing, so the rest of the work is good old Do-It-Yourself JavaScript with little code. In my opinion it is more faithful to the promise "Just the UI" than React is. virtual-dom throws instructive errors in the event of invalid input, and there are some very useful libraries built specifically for virtual-dom.

Another crucial tool is RxJS, which makes it possible to avoid writing low-level event utilities that other frameworks have to provide. It often almost removes the need to have a framework in the first place.

Model-View-Intent is just an experiment that seems to be working. Unidirectional data flow with the Virtual DOM certainly exists outside the context of React and Flux. There are many possible variations of this architecture, and as frontend technologies normally go, this might evolve significantly in the future. These are exciting times with a lot still to happen.

- Andre MedeirosUser Interface Engineer