Do you feel the pain? The pain of banging your forehead against the university walls because it is more pleasurable than struggling to get your bachelor's or master's thesis done.

In the past decade or so I have instructed over twenty theses. In practice, I have been doing my best to help thesis writers to overcome unnecessary obstacles. I say unnecessary because thesis writing should be inspiring, fun, exciting, and very, very useful for your future career (even if you never become an academic).

Here's what I have learned as an instructor:

Four common pitfalls in writing a thesis

1. "My thesis will define the rest of my life!"

Do not let the thesis become more important than it is. Yes, the thesis is one of the highlights of your studies, but it is only one part of your studies. The point of a thesis is to demonstrate that you can tackle an interesting topic in an academic manner, i.e., you can do research. It won't define who you are, it won't define your career, and no one has ever won a Nobel prize based on their thesis. Put the thesis into context and take a more relaxed attitude towards it. The result is that your writing becomes easier, faster, and better. It is only a thesis. Sit down and just do it!

2. "My results are the most important part!"

Well... no. The point of a thesis is to show you can do research and document it in writing. If your research question, methodology, and positioning are well done, the results are not that important. Especially if you analytically discuss the results and show that you understand why the results are what they are. No one is expecting a thesis worker to come up with a ground breaking scientific contribution, so take it easy.

3. A laundry list of literature.

The literature study in your thesis should not be a boring list of references you dug up from Google Scholar. The literature, i.e., other people's work, should be part of your narrative. You should position your work in relation to other work. Think of it as a large puzzle where other people's work form 99% of the puzzle pieces, and the last piece is this thesis of yours. Your job is to describe the picture that the whole puzzle forms (the broad topic of academic research) and then you describe the major existing pieces of this puzzle (academic literature, previous work, existing software, standards, patents...) and then explain how your thesis is a missing piece that helps form the bigger picture (it is probably a small piece, but a missing piece nevertheless).

4. Writing for no one.

What is the easiest way to write really boring text? Write it for no one in particular. Boring text creates a bad thesis. More importantly, it makes it harder for you to understand what is relevant and what is not. Therefore, define an audience and state it in your thesis. Are you writing for fellow software engineers? Are you writing for people who are experts in one field but not in the one you are researching? Is your audience academic or business people? Once you have an audience in your mind, put yourself in their position and think what would they want to know. This will be your guiding light throughout your writing: what is my audience going to do with this piece of information? NOTE! In practice, you have an audience of one: your professor is probably the only person on this planet who will read your thesis. Therefore, it is very important to know what your professor is looking for in a good thesis and what research and literature s/he thinks is relevant.

Great, now you have an idea what pitfalls to avoid. But how to write a great thesis?

The wrapping is more important than the contents

I believe in a crystal clear structure in a thesis. Why? Because most people do not read a thesis like a detective novel: in a linear way from page 1 to the last page. Observe yourself picking up someone's thesis. Most probably you start looking for the abstract or thesis statement to see whether the work is of any interest to you. Then you jump into results. Then you might skim over the methodology to figure out whether you believe in the results, and then you jump to the list of references to see whether they cite the work you are familiar with.

My point is that everyone who ever picks up your thesis will read it in a non-linear way. Therefore, the structure and the table of contents are very important for the reader to be able to jump back and forth and to figure out with minimal effort the gist and quality of your research.

There is another reason for having a clear structure. Academic work is all about making the research process clear and transparent so that your findings can be scrutinised and the scientific community can believe in your work. It is the core of the "scientific method", to document one's research in a way that other scientists can understand how you came up with your results and build on top of them. A great thesis has a clear structure because it demonstrates to your professor that you understand this fundamental point of scientific work. In other words, you can do academic writing.

What makes a great thesis structure?

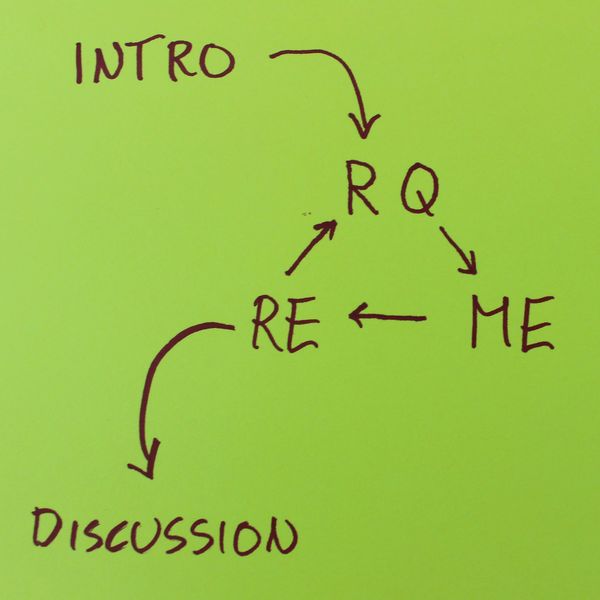

In the core of your thesis you have a triangle of three key things: the research question (RQ), the research method (ME) and the research results (RE). The RQ defines the ME which produces the RE which answers the RQ. In other words, you ask a research question (the missing piece of the puzzle), and to answer that question you choose certain methods, and those methods obviously produce some results, which are the answers to the original research question. Yes, it is as simple as that.

The three parts are, of course, interconnected. So if you change your method, you better check whether you are still answering the research question and whether you are still producing the results you are looking for. I always recommend people to write down their first draft of these three components on the very first day of writing. Writing a thesis is very much about iterating these three components and tweaking them into a neat academic package.

The core triangle of any thesis: Research Question, MEthodology, and REsuts.

The core triangle of any thesis: Research Question, MEthodology, and REsuts.

What about the Introduction, Literature and Discussion parts of my thesis?

The Introduction section of your thesis is where you paint the big picture and connect your work into the bigger questions and issues out there. The literature section is where you position your work (see above), and the discussion section is where you take your results and connect them back to the big issues you described in the Introduction. Let's use the puzzle metaphor again. The Introduction is looking at the big picture of the puzzle with 99% of the pieces in place. The literature section is describing the most important pieces of the puzzle and the ones surrounding the missing piece. Your RQ is framing the missing piece, your ME is describing how you will fill that hole, and your RE is the final missing piece. Then your discussion section at the end of the thesis is stepping back and looking at the big picture of the puzzle now with your little piece in it.

Jump-Starting Your Thesis Writing

Let's take everything I mentioned above and turn it into the first pages of your thesis and the first version of your thesis format. Open your text editor. Write the following section headers:

- Introduction

- Literature

- Research Question

- Methodology

- Results

- Discussion

- References

Next, take each section, and underneath the header, write in bullet points 3-5 things you will write about under that section.

Next, see whether there are some obvious sub-sections. For example,

1. Introduction1.1 The effects of climate change1.2 Rising number of cyclists in European cities

For each sub-section, write 3-5 bullet points that describe what should be discussed under the sub-header.

Now you have a skeleton of a thesis that will help you address the writing piecemeal. You can choose small parts here and there to work on, and you will have a good structure to keep the parts together to form the whole thesis. Every now and then revise the whole super structure to make it balanced and to support your work. For example, many students decide that a the research question is a sub-section under the Introduction (e.g., 1.3. Research Question). Some writers feel more comfortable having the literature part also as a sub-section of the Introduction.

Don't forget to check with your professor whether they agree with the structure you have. For example, some professors require a Conclusions section in the thesis, and some disciplines of research typically separate the analysis of results from the actual Results section.

Final tip: some sparring questions

My last tip to you is a set of sparring questions for each top header.

1. Introduction

Why is this research important? Is there a bigger phenomenon that this research of yours is part of? Why people in your profession should care about this thesis?

2. Literature

What has been done related to this (mainly in academic publications)? What do the authors say about the topic? How does your research question relate to these previous studies? How do you apply them or add to them? Based on what they say, what do you say? (Tip: find an actual researcher that has studied your field and ask her/him for relevant literature. You save weeks of work once you find an expert).

3. Research Question

Based on what other people have studied before, what is the question that no one has really answered yet? What is the main question, and what are perhaps the two or three sub-questions that you need to answer to be able to answer the main question? Look twice what you write in your RQ, because you will have to answer these questions :)

4. Methodology

How do you find an answer to the research question? How do you gather data? From where do you gather data? How do you analyze the data? Out of all the methods in the world, why did you choose this one? What is good about it and what is not? What were the alternative methods, and what were their pros and cons?

5. Results

What is the answer to the research question? What are the answers to the sub-questions? Keep this simple and clear.

6. Discussion

How could someone criticize your results? Are they internally valid (the data was gathered and analyzed correctly)? Are the results externally valid (can they be generalized and how)? Based on the results, what can you say about the bigger picture you described in your introduction? How could someone apply your results for further research? Or perhaps apply in a non-research context (e.g., in a company or in everyday life)?

Take each section at a time and one question at a time and answer them in bullet points. Suddenly you have several pages of your thesis ready. Then turn the bullet points into actual text that is easy to read (remember to keep your audience in mind). And that is how you climb the thesis mountain one step at a time.

Let me know if you found this blog post useful and if you have suggestions or other comments. I hope these tips and points help you get your thesis done and over with, so that you to focus on (perhaps) the more important things in life :)

- Risto SarvasService Designer, Professor, Company Culture Engineer